An End to the Drama

As the curtain falls on 2022, what can we expect from 2023?

BY MICHAEL ABBOUD, CFA

Chief Investment Officer & Senior Vice President

For equities and fixed-income markets, 2022 certainly had its share of drama. Like the ghost in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, record-high inflation numbers frequently appeared throughout the year. And just as in the play, their appearance sowed confusion and fear in markets.

The longer this inflation-induced uncertainty persisted, the greater the odds of loss became. The bull market that arose out of the pandemic abruptly ended when investors were forced to grapple with a massive reversal of financial conditions. As a product of this struggle, stocks and bonds delivered their worst combined performance since 2008.

We gladly draw the curtain on 2022 and find reasons for optimism and opportunity in the new year. The following roadside markers offer a historical perspective on the current bear market journey.

Consecutive Annual Declines Are Rare

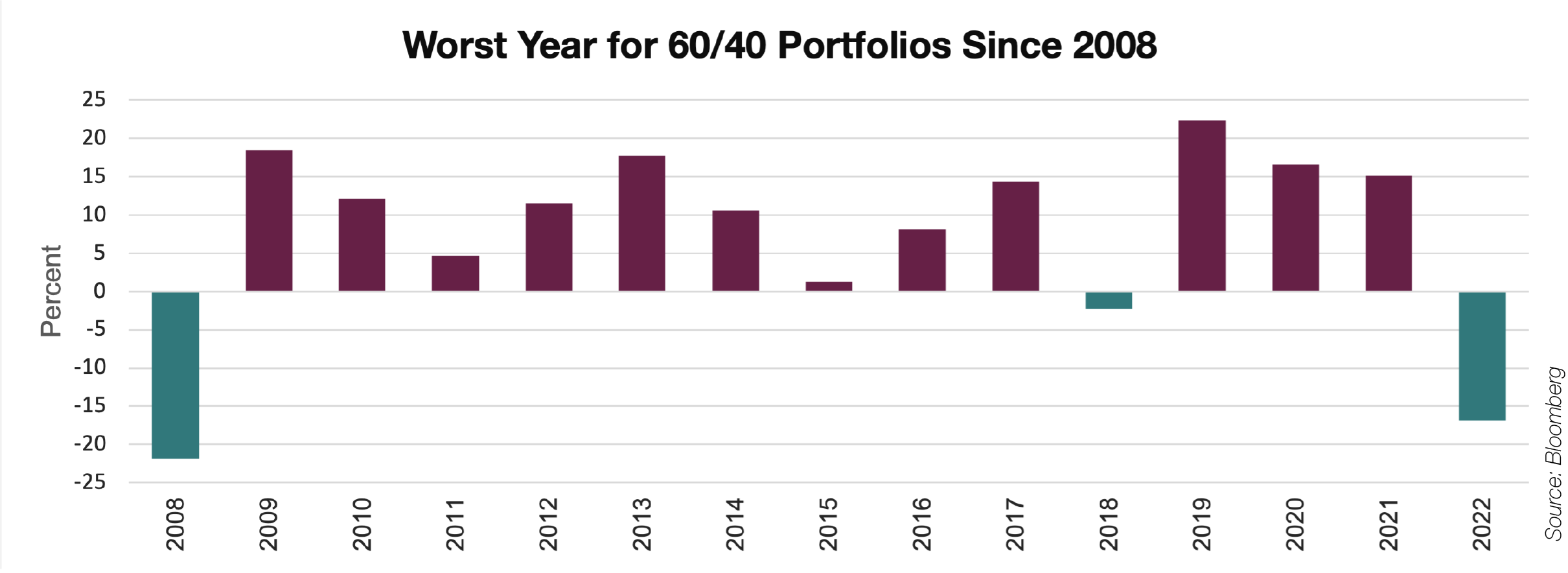

The classic “60/40” portfolio has long been considered the gold standard for investors with moderate risk tolerance. Its 60% allocation to equities has historically offered investors exposure to capital appreciation, and its 40% allocation to fixed income has provided income and a reduction in the portfolio’s overall risk. Yet despite its enduring popularity, over the past year, many pundits have questioned whether the 60/40 portfolio might be dead.

The reason? In 2022, the 60/40 posted its greatest decline since 2008, falling by approximately 16% (see chart). In fact, 2022 marked the fourth-worst year on record since 1926. However, when the 60/40 portfolio has fallen by greater than 10%, there have only been two instances in which the following year’s return has also been negative, specifically, during the Great Depression and the Great Recession – periods associated with profoundly greater economic stress than today.

Even if you consider bonds and stocks separately, history is equally encouraging. This past year bonds posted their second negative return year in a row, a dismal record not seen since 1958-59. Bond markets have never registered three consecutive years of negative returns. As for stocks, since 1928, they have only declined two years in a row on four occasions, with each down year three times as likely to be followed by an up year.

Nothing Lasts Forever

The current bear market has dragged on for 12 months, with the S&P 500 dropping by approximately 25% at its lowest point. Yet as painful as the past year has been, it’s worth putting these numbers in context. Since 1942, the average bear market has only lasted around 11 months, with an average loss of 32%. There may be more volatility and further declines ahead, but history suggests that much of the damage has already been done.

Is Recession Inevitable?

The Fed and other central banks have sent a clear message that they will sacrifice economic growth on the altar of price stability to avoid the policy mistakes of the 1970s. To that end, the key macroeconomic question is no longer when inflation will peak but whether the highest inflationary environment in 40 years can be tamed without a recession.

The Case for a Soft Landing

Despite the Fed’s less-than-stellar track record at engineering a “soft landing” and avoiding recession, many economists believe this tightening cycle could be different. In particular, they cite several factors, including: a belief that current inflation mostly reflects pandemic supply imbalances that will eventually self-correct, an employment-to-population ratio that is not excessively high, and longer-term inflation expectations remain reasonable.

The case for a soft landing is built on the premise that the U.S. economy will have an extended period of positive but below-average growth. That slower growth will eventually help alleviate an overheated labor market, bringing down wage inflation and, in turn, headline inflation. There are currently six million more job openings than unemployed workers, which should provide the Fed with room to cool the labor market. The slack in the jobs market could allow the Fed to bring wage growth in line with levels compatible with their 2% inflation target.

If the Fed is successful in this endeavor, inflation as measured by the core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index should decline from the current 4.7% annualized rate to roughly 3% by the end of this year. This decline would be due to softer wage growth and goods inflation continuing to moderate as supply chains continue to heal. Services inflation could fall meaningfully, as the official data catches up with real-time numbers, particularly in areas such as shelter and health care costs.

The Case for a Hard Landing

History sides with those who contend that a recession is likely. Eleven of the last 14 tightening cycles have ended in a recession. Furthermore, recessions have always occurred following periods when inflation was greater than 5% and when the unemployment rate has risen by 1% from its lows, which the Fed forecasts will occur later this year.

There are many other signals that indicate a recession is likely. Longer-term bond yields peaked in late October, and now most of the yield curve is inverted, which has historically been one of the best recession indicators. Furthermore, real-time economic data, including manufacturing, housing, and consumer confidence, are all already at recessionary levels.

Even if a recession occurs in the first half of 2023, there are many reasons to believe it will be relatively shallow, especially when compared to the hard landing of 2007-09. The U.S. economy as measured by GDP expanded by a 2.6% annualized rate in Q3 2022, and unemployment remains near historic lows. Overall, the financial system is in much better shape, with strong corporate and consumer balance sheets serving as buffers to economic weakness.

Final Thoughts

The economy and markets have acted like a ship trying to right itself from the macroeconomic waves left in the wake of the pandemic. Given the extreme monetary and fiscal stimulus undertaken to stabilize the economy in 2020, this past year could be viewed as an adjustment to those measures.

Despite initially being slow to react, the Fed has ultimately responded to the highest inflation in four decades with an equally aggressive rate tightening cycle. As a result of this “rip the Band-Aid off” approach to monetary policy, it appears the Fed may have avoided the stop-and-go monetary policy mistakes of the 1970s, thus also averting a potential double-dip recession and a protracted period of below-average equity returns.

The war on inflation may not be over yet, but it does appear that the Fed is winning. In June, annualized inflation peaked at 9% and currently stands at 7%.

A closer analysis of the underlying inflationary components of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), reveals that the Fed may be closer to achieving its 2% inflationary target than the current headline 7% number would suggest. With the annual rate of growth in the CPI over the past five months at 2.45%, the Fed is already close to its 2% target.

Using current numbers for the CPI shelter category (versus the official data, which is known to lag), would have resulted in month-over-month inflation declining last month as measured by core CPI. Consensus estimates for inflation in the year ahead recognize this progress and forecast inflation to be roughly 3% by the end of this year based on the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index (PCE), the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation.

To engineer a soft landing, the Fed must get the glide path correct. It would not be surprising for the Fed to run out of runway as in 1974 when it continued to tighten after the recession began. However, policymakers have a more sophisticated understanding of both inflation dynamics and their policy tools, as well as better real-time data, than they did 40 years ago. Because of this, the economic picture should give the Fed the justification to pause by Q2, then begin to pivot policy.

Given the stock market historically bottoms four months after the last rate hike, equities could start to recover by this fall. Until then, inflation may haunt markets a few more times through the final acts of this bear market, but these visits should not provoke an overreaction as the threat of inflation continues to decline in the new year.

MICHAEL ABBOUD, CFA

Chief Investment Officer & Senior Vice President

(918) 744-0553

MAbboud@TrustOk.com