Finding Meaning in the Noise

By Zac Reynolds

When I wrote in this space last October, stock market averages had fallen sharply in August and September and investors were fearful of further declines. My message was to embrace pullbacks in the market as opportunities rather than see them as reasons for anxiety. In other words, investors should try to train themselves to feel happy when the market goes down.

From the end of September 2015 to mid-September this year, the S&P 500 has rallied more than 15%. Bonds have also performed well, which means that pretty much everyone’s investment assets are worth more today than they were 12 months ago. Investors who embraced the pain last fall and stayed the course have been rewarded while those who gave in to fear and sold have missed out.

But now that stocks are, on average, 15% more expensive than they were a year ago, how should investors be feeling about the markets? Has the economy really improved so much that stocks deserve a 15% premium to where they were 12 months ago? Or were stock prices unreasonably low last fall and now they have just returned to normal?

The answers to these questions are not easy. In the long run, a company’s stock price tends to reflect the underlying economic value of the firm. In the short run, however, stock prices are like a voting mechanism in a popularity contest (or presidential election) subject to the whims and emotions of humans who do not always behave rationally.

For example, on September 9, the S&P 500 fell by nearly 2.5% after going 50 days without a move – up or down – of 1% or greater. Headlines and talking heads in the financial news blamed the move on comments made by a Federal Reserve regional bank president that were more “hawkish” than expected about the possibility of a September rate hike. The very next trading day, the S&P 500 regained 1.5%, and the financial media credited the move to a different Federal Reserve member who made more “dovish” comments. The following day, the market fell again, and this time the move was blamed on a drop in oil prices.

While Federal Reserve interest rate changes and oil prices certainly matter to the economy, there were plenty of other days where a Fed governor gave a speech or oil prices moved up or down where the stock market didn’t react in a significant way. It just isn’t accurate to assign one overall reason for a market move caused by tens of millions of market participants buying and selling stocks, each with different risk tolerances, time horizons, and motivations for their trades.

Those casting about for reasons for a market move are falling prey to the logical fallacy expressed by the Latin phrase post hoc ergo proctor hoc. In other words, the financial media looks at what the market is doing and then tries to come up with a reason. They are confusing correlation with causation. But you can’t blame them – after all, a headline writer can hardly write “Dow Drops 150 But We Don’t Know Why.”

What you can do is ignore the noise. The trite, but true, reason the market goes up is because there are more buyers than sellers on that particular day (or, more accurately, those buyers are more motivated on average than sellers and willing to take higher prices). Those buyers may have good reason, or it may just be sunny in New York (some studies have shown a meaningful positive correlation between sunny weather in a country’s primary financial market city and daily stock market returns; other studies claim the relationship is just…noise).

The Long Term

Rather than worrying about the day-to-day popularity contest the market runs, a more useful approach is to measure the worth of each investment, and the market as a whole, in terms of its long-term potential. Fortunately, we have more tools available, and higher confidence in our predictions, when we switch the focus from weeks or months to years or market cycles.

For example, the S&P 500 is trading at around 20 times its earnings over the last 12 months, higher than historic averages of around 16 times. Over the short run, this information has fairly limited predictive value. Sure, we can say that the market looks a little expensive, but you may recall that the earnings multiple expanded to over 30-times earnings during the tech bubble in the late 1990s. I wouldn’t bet on that happening again, but it’s certainly possible that today’s somewhat expensive market could go up to even richer levels next year.

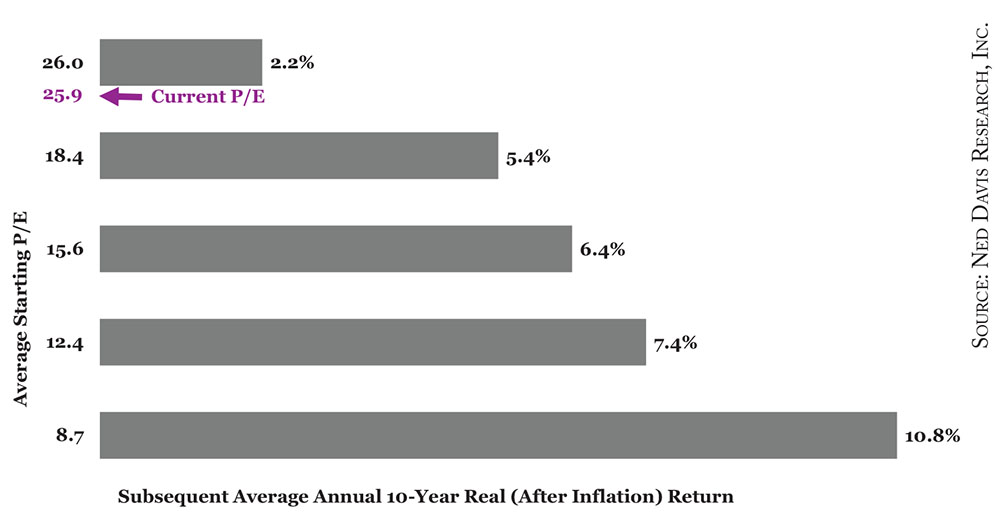

While one-year returns can’t be predicted with much accuracy, stretching out our perspective to look at returns over the next 10 years allows us to use valuation tools to forecast returns much more confidently. Instead of the shorter term one-year P/E ratio, the chart on page 3 shows price divided by inflation-adjusted earnings over the previous 10 years (this is also known as CAPE or Shiller’s P/E). There is a strong relationship between Shiller’s P/E at any point in time and subsequent real returns over the next 10 years. Unsurprisingly, markets have the highest 10-year returns following periods when price-to-earnings multiples are in the lowest (cheapest) quintile, averaging 10.8% a year above the rate of inflation.

Unfortunately, today’s price-to-earnings multiple based on 10-year earnings is nearly 26, putting us squarely in the most expensive quintile. Historically, S&P 500 returns in the decade following valuations at today’s levels average just 2.2% per year over the inflation rate.

Other measures are also flashing caution signs. S&P 500 market cap as a percentage of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) is close to 100%. That measure has only exceeded 100% once since World War II – again, in a stretch leading up to the bust of the tech bubble.

There is, however, a major mitigating factor that must be considered when examining valuation measures today – interest rates. At today’s near-record low levels, rates are extremely supportive for the economy and the stock market as consumers and businesses can finance purchases at very low cost. Some strategists argue that traditional valuation methods can’t be trusted because low interest rates forced by central bank intervention means there is no alternative to buying stocks.

Perhaps. But I am always skeptical when the argument for the market going higher is “it’s different this time.” My expectation is that low rates will provide enough of a cushion to boost equity returns significantly higher than the 2.2% implied by the chart, but the market’s price-earnings multiple ultimately trends downward toward historic averages. Unless the economy were to significantly accelerate, leading to higher earnings per share, this scenario would still mean below average returns for stocks over the next decade.

Of course, lower average returns have implications for investors planning for the future. Those counting on historically normal returns should consider adjusting their expectations in light of current stock market valuations and interest rate levels. It may be necessary to bump up savings rates or plan to work an extra year or two before retirement. Fortunately, a small course correction made early can help avoid painful decisions later. If you want to talk about what lower returns might mean for your individual situation, please reach out to us.