Getting Banks Back on Track

Understanding Recent Bank Failures and How They Compare to 2008

BY REBECCA MITCHELL, CFA

Vice President

Like most children, I watched many Disney movies. And while each film arguably has a lesson behind it, Disney likely never intended to give children an early study on banking. Yet, for me at least, Mary Poppins provided my earliest illustration of how banks function.

Dick Van Dyke’s character Mr. Dawes Sr., of Dawes Tomes Mousley Grubbs Fidelity Fiduciary Bank, sings to the children about how critical the deposits of banking customers are for financial markets to operate and how those deposits are invested in businesses and other ventures.

The story of the Banks family reaches its climax when the children unintentionally start a run on the bank. Mr. Banks is fired, but in pure Disney fashion, everything is tied up nicely for the family. However, this is where artistic liberties take us away from the seriousness of a bank run.

Banks are a crucial piece of our financial markets. They give consumers a place to store their cash safely and give individuals and companies loans to buy houses and start businesses. When consumers become fearful in large groups and request their deposits in a short period of time, instability can occur in the form of bank runs.

In March, we witnessed the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history when the FDIC took over Silicon Valley Bank (see Chart A below). This failure followed the announcement that Silvergate Capital, a cryptocurrency clearinghouse, was shutting down. The weekend after the government took over Silicon Valley Bank, the government also took control of a second bank, Signature Bank. There are lingering concerns that other banks might fail.

To understand these events, remember that banks borrow short and lend long, meaning they borrow the funds of those with checking and savings accounts to invest in longer-term home loans, business loans, Treasurys, etc. Even the healthiest banks do not have enough cash to make all their depositors whole in a few days. To help protect depositors from the risks of the assets banks invest in, there are regulations in place, including requirements for banks to have a certain amount of cash on hand and FDIC insurance for depositors. This insurance is limited to $250,000 per depositor per institution.

History of Silicon Valley Bank

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was a regional bank that started in the early ᾿80s. SVB had a history of investing its own money in venture capital (when it was legal), making it well-known for supporting venture capital investing and startups. The bank continued to grow through the years. The growth accelerated with the partial rollback of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2018, which no longer applied to smaller banks.

With interest rates low and the tech sector booming, SVB went from having $45 billion in assets in 2016 to $200 billion by the end of 2020. With this growth, most SVB clients had more than the FDIC insurance limits of $250,000 at SVB. Among those customers above the limit were many companies, including well-known startups such as Roku and Etsy.

SVB invested some of its funds in 20- and 30-year U.S. Treasury bonds. When these investments were made, longer maturities earned more interest. However, once the Fed began raising rates, it put pressure on the tech and startup industries. Ideas that made sense when the debt was cheap were less attractive at higher rates. Tech companies started laying off workers, and some startups closed altogether, leading SVB customers to take cash out of the bank. SVB needed to raise cash by selling bonds out of their Treasury portfolio.

Silicon Valley Bank Collapse

On March 8, it was discovered that SVB had sold a $21 billion portfolio of U.S. Treasury Bonds at a $2 billion loss in one 24-hour period. This news made anyone with a stake in the bank nervous. They believed that if the bank had to sell a portfolio of this size this quickly at a loss to meet its obligations, it must be in terrible shape. Through social media, concerns were shared among customers, causing a contagion. Customers began to worry, and they proceeded to withdraw their funds from the bank, creating a bank run on SVB. Roughly $42 billion of deposits, approximately 24% of total deposits, were withdrawn on March 9.

Additionally, SVB’s stock crashed that same day. By March 10, withdrawals were happening so quickly that the government stepped in and took over the bank. Its collapse left investors wondering if other banks would soon follow suit.

Following the announcement that the government was taking control of SVB, there were two schools of thought regarding what might happen next. The first was that the FDIC should only insure SVB depositors up to the standard limit. As one of the jobs of the FDIC, this is how the agency had dealt with many previous failed banks.

The second school of thought was that if the FDIC did not do something about the large number of uninsured deposits at SVB, it could cause panic for depositors at other banks and create a run on multiple banks. SVB is different from other banks because a disproportionate amount of its deposits were above the insured amount of $250,000. Per its last regulatory filing, 85% of its deposits exceeded the FDIC-insured limit. One reason behind this was SVB’s relationship with many technology and biotech startups that used SVB as their business bank. If these companies were not going to be made whole, they were at risk of being unable to make payroll or fulfill other financial obligations, causing a massive ripple effect throughout the broader economy.

On March 12, the government responded to the escalating concern by taking significant action and making all of SVB’s depositors whole, even those that exceeded the $250,000 limit. Additionally, the government took control of a regional bank in New York, Signature Bank, and has committed to making its depositors whole, too. The government hopes to prevent banks from making a fire sale of their bond portfolios as SVB did, causing panic among investors and depositors.

Making depositors whole requires banks to shoulder the costs as a group. Banks pay into a shared fund for deposit insurance. When a bank fails, depositors are made whole from that pool of money. So far, the current situation is effectively banks bailing out banks.

2008 vs. 2023

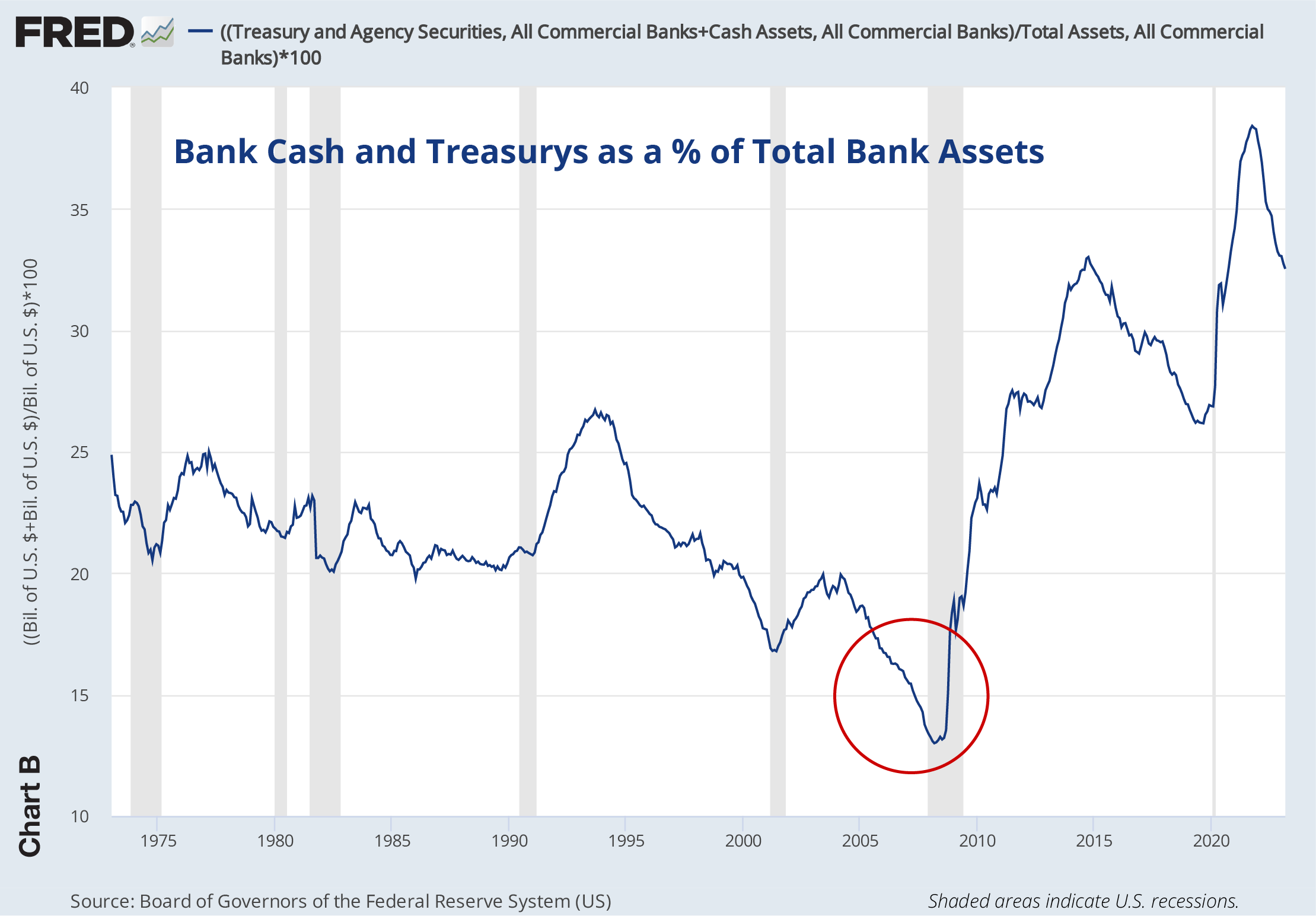

While many people have compared this year’s bank failures to 2008, there are significant differences to consider when comparing the banking sector then versus now. In 2008, banks took on more liability by offering riskier loans and having fewer low-risk assets on their balance sheet. As you can see on Chart B (see below), banks had the lowest amount of cash and Treasurys as a percentage of total bank assets in 2007 and 2008, meaning the banks were highly leveraged and at higher risk of becoming insolvent. Using the same chart, you can see that today banks have a much higher percentage of their assets allocated to Treasurys and cash, which are substantially safer assets.

![]()

The issues banks are facing today are different. Banks do not have the credit risk they had in 2008, but they face a lot of duration (interest rate) risk with their bond portfolios. Since the Fed has increased rates at one of the fastest paces ever, that has put much pressure on those longer-dated Treasurys that so many banks hold. Bond prices decrease when interest rates increase, meaning banks are carrying Treasurys with unrealized losses on their balance sheets. Bond price decreases are not an issue for banks when they can hold the assets to maturity and get their money back. The problem arises when depositors start pulling out so much money that it exhausts the bank’s cash on hand, causing them to sell Treasurys before maturity. This situation is why risk management is so important in banking. SVB is an example of where the client base is concentrated in a particular industry, causing the cash flow needs to exceed what the bank can provide.

What’s Next

Initially, the FDIC took control of SVB and created a new entity called Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara to hold the bank’s assets. Since the initial FDIC receivership, $72 billion in SVB assets have been sold at auction. The winning bidder, First Citizens Bancshares, acquired the SVB shares at a substantial 23% discount and with favorable financing terms, concessions which reflected the lingering fears about SVB and its assets.

While there could be additional bank failures, the fact that the FDIC stepped in so quickly with SVB and Signature indicates that they would do the same for other banks. During extreme situations, the government has a lot of power to stop panic and contagion.

The turmoil in the banking industry is a sign to the Federal Reserve that it may be time to slow rate hikes. However, inflation is still higher than the current Fed funds rate and needs to decrease more. The bank collapses have signaled the Federal Reserve that they might need to reevaluate their rate path.

Before these recent bank failures, the futures market was pricing in three to four rate hikes by 2024. Now, it is pricing in only one additional rate increase. In other words, the market indicated that the Fed would continue to try and slow the economy by increasing interest rates. Still, the events that have unfolded in the banking industry could send a message that they have gone far enough and that further increases could do more harm than good.

The Justice Department will investigate the SVB’s collapse to determine if any executives acted in their own self-interest during the crisis. Additionally, they will review whether the bank took more risks than it should have. The 2018 regulatory rollback may also be reviewed to see if it opened the door for regional banks to be too lenient with risk management. In 2008, large banks were supported by the government and labeled as “too big to ignore.” Some have labeled SVB as “too big to ignore.” There have been other bank failures in the last decade, but none of this magnitude.

Regulation may increase again for regional banks. Funding costs may increase for the industry, there may be new requirements for banks with higher unrealized losses in their portfolios than peers, or banks could face more scrutiny for having a high percentage of deposits above the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit. That insurance limit could also change.

Consumers may change their preferences and move their funds to larger banks that face higher regulatory scrutiny and are considered “too big to fail.”

In the film Mary Poppins, the Banks family received their happily ever after from a mysterious nanny. So far, the FDIC has played the role of Mary Poppins in 2023, rescuing SVB depositors.

REBECCA MITCHELL, CFA

Vice President

(918) 744-0553

RMitchell@TrustOk.com