Short-Term Pain for Long-Term Gain

By Nick Gallus

A close look at where the interest rates may be headed

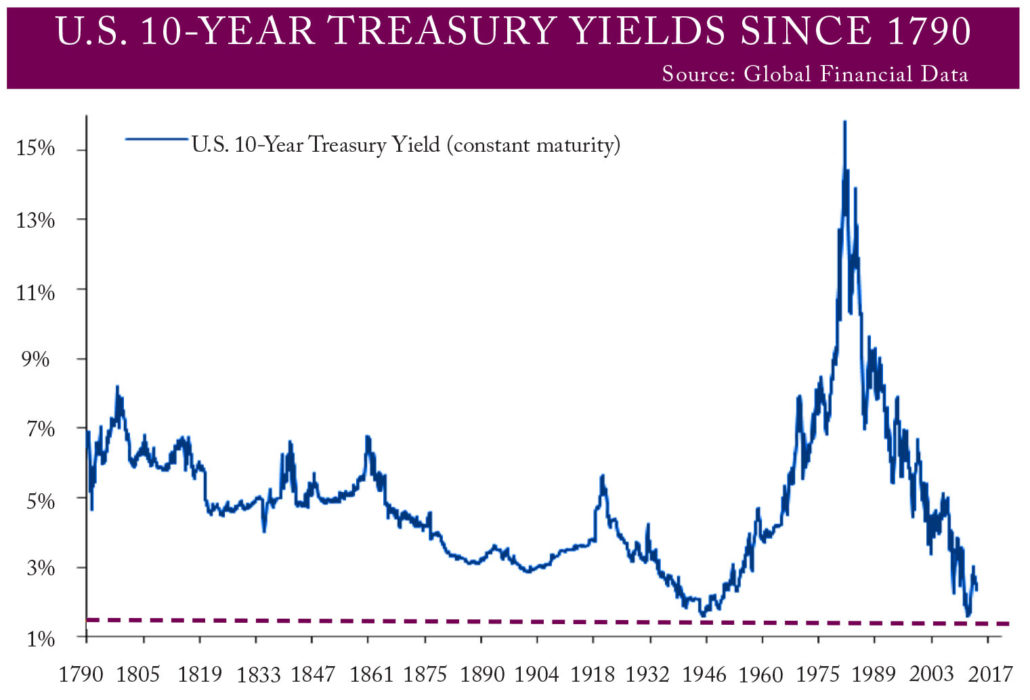

Since the election, there has been much talk about the spike in interest rates. This is not surprising since the Federal Reserve more than doubled its benchmark interest rate to a range of .75-1%, while the 10-year Treasury yield improved from 1.8% on November 7, the day before the election, to 2.4% currently. As much as these rate hikes have sparked conversation, interest rates are still very low by historical standards. This is particularly true once inflation is factored into investors’ expectations of a real (i.e. above inflation) rate of return from bonds. The perception that interest rates have increased meaningfully is only true when compared to the extremely low levels reached in the summer of 2016, when the 10-year Treasury bond yield hit a low of 1.34% on July 6, 2016, in the aftermath of the “Brexit” vote. In fact, that 1.34% yield was the all-time low 10-year Treasury bond yield, going back to 1790.

LONG-TERM PERSPECTIVE

While a 1.34% yield is extremely low, interest rates have a history of trending up and down in long, drawn-out “secular” cycles. As seen on the chart (Page 2), the 30-year treasury bond yielded just 2.1% in April 1946 following the end of World War II; it increased to 3.1% 10 years later and eventually peaked at 15.2% in the fall of 1981 after a decade-plus of rising inflation. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, long-term bonds were often referred to as “Certificates of Confiscation” due to their poor history, generating returns below inflation for investors.

Today, the opposite seems to be true. The United States experienced a 35-year bond bull market from 1981 to 2016 in which long-term interest rates overall trended lower (along with inflation), generating very good returns for investors. Bonds today are generally viewed as safe havens to park cash, with investors only somewhat concerned with inflation and credit (i.e. repayment) risks. Looking forward, things don’t look so rosy for fixed income investors compared to the last 35 years. With inflation being the most significant long-term driver of interest rates, the low inflation years following the financial crisis of 2008 appear to be in the rearview mirror with green shoots of inflation picking up in the form of wage increases and rising home prices. Furthermore, with economic growth being the second significant driver of interest rates, increased business and consumer confidence are returning. Inflation is expected to increase to 2-2.5% annually in the near term. Rising inflation can hurt bond prices in the short-term as prices move opposite of interest rates.

Does the 1.34% yield on the 10-year Treasury bond following both Brexit and the election of Donald Trump mark the turning point for a sustained rise in interest rates going forward? No one knows for certain, yours truly included. It’s important to remember that there are thousands, perhaps millions, of interest rates in the world – not alone, monolithic interest rate that the Federal Reserve controls with an iron fist, as is often implied by media coverage. It is notable to recognize that two-year Treasury yields hit a low of 0.15% way back in 2011 (currently 1.3%), and the five-year Treasury yield hit a low of 0.54% in the summer of 2012 (currently 1.9%). That was four to five years before the 10-year Treasury yield hit its low in 2016! The “reach for yield” has been alive the last several years with investors purchasing longer-maturity bonds rather than short-maturity in order to earn a higher yield, despite greater risks with long-maturity bonds.

STOCKS VS. BONDS

Traditionally, by investing in high-quality bonds, investors have made the conscious tradeoff of (1) having a lower risk of principal loss in exchange for lower returns (i.e. yields) relative to stocks, and (2) it was reasonable for investors to expect a modest return above inflation on bonds.

However, these two basic assumptions about investing in fixed income are not so easily taken for granted given the current low starting level of interest rates. With the Fed raising its target rate on short-term Fed funds (borrowing between banks) to a range of 0.75-1.0% in March, we are clearly now on the path back to “normal” interest rates. But with inflation likely to be above 2% in the near-term, we are not fully there yet.

At Trust Company of Oklahoma, we carefully consider the risk of any investment, and in the context of rising interest rates, we consider the primary risk to be a permanent loss of purchasing power from a sustained rise in inflation.

Market participants currently expect the Fed to raise short-term rates twice more in 2017, and continue to raise rates further in 2018 and 2019. Research shows that over the last eight rate-increase cycles from 1958 through 2006, the 10-year Treasury bond on average experienced a total return of -8% over a 15-month period as it adjusted to higher rates. A return of -8% is worth paying attention to, especially for an investment that many hold partly for its stability.

This is best viewed as Short-Term Pain for Long-Term Gain. If interest rates continue to increase further, bond prices may be negatively impacted in the near-term. Yet, so long as an investor’s time horizon is longer than the potential negative short-term impact to bond prices, higher interest rates will benefit an investor’s portfolio as bonds come due and are reinvested at higher rates with all else equal.

Similar to how equity investors need to have at least a 10-to-15-year time horizon to ride out potential stock price volatility, fixed income investors should think similarly when considering bond price volatility.

For example, if a bond investor has a 10-year time horizon before funds are needed, she could invest in a 20-year maturity bond at a fixed interest rate. If inflation and interest rates then increase after purchase, the value of the bond will decline and potentially be sold below the purchase price in ten years, resulting in a loss of principal.

Alternatively, that same investor could purchase a five-year maturity bond at the outset, whose price will be less significantly (and temporarily) impacted if rates increase. She will also receive the benefit of reinvesting at a potentially higher interest rate available at the five-year maturity when the money is reinvested for years six through 10. Not only will the second scenario fully preserve the investor’s principal, but it could potentially earn a higher yield as well, depending on how much market interest rates increased over the investment period.

MANAGING RISK

There are two important investment strategies TCO recommends to manage the risk embedded in low-interest bonds that currently dominate the market. The first is that we eschew long-term (e.g. 20-30-year maturity) bonds because of the potential price risk given the low starting point of interest rates. At that length of maturity, relatively modest changes in long-term interest rates can have a significantly negative impact on bond prices, which could then take 20-30 years to recover if held to maturity. By investing in short to intermediate maturity bonds, we can more frequently reinvest principal at higher rates, if they were to occur, while forgoing somewhat higher yields available from long-maturity bonds.

Secondly, we recommend not blindly investing in fixed income index funds, which over the last several years have become more heavily weighted in long-term government bonds paying low-interest rates. After the financial crisis, the U.S. and other federal governments issued trillions in additional debt in order to fund huge budget deficits. Subsequently, many trillions of these bonds were purchased by the Federal Reserve via its “quantitative easing” program, in effect buying these bonds no matter the price in order to purposefully drive down interest rates. In addition to the Federal Reserve, large U.S. banks also purchased billions of government bonds, which sit on their balance sheets as liquidity to be available in case another financial crisis were to occur.

Effectively, regulations mandating these piles of liquidity have created more large “non-economic” buyers of low-yielding government bonds. We strongly dislike purchasing an investment in which we compete against big buyers of that investment who frankly don’t care what price they buy or sell. Rather, we prefer to pursue, at minimum, a fair return on our investments considering their risks, not simply whatever return happens to be available.

After everything investors have been through the last 10 years, returning to normal (higher) interest rates, where investors can expect a decent real return, is what we should all hope for. That may mean carefully avoiding unattractive risks and taking short-term pains for longer-term gains.

Nick Gallus

Vice President

(918) 744-0553

NGallus@TrustOk.com