Should Anyone Buy Bonds?

By Bob McCormick

Past performance is not a predictor of future results. We know what this means, but our mental calculators have a hard time accepting this as fact. We often frame even the most basic investment decision of stocks vs. bonds through the rear-view mirror of just-passed returns. Recent markets are a good example. Bonds (Merrill Lynch Govt/Corp) have averaged a paltry 2% return over the past five years, while stocks (S&P 500) have returned a strong 15%. This begs the question: why buy bonds?

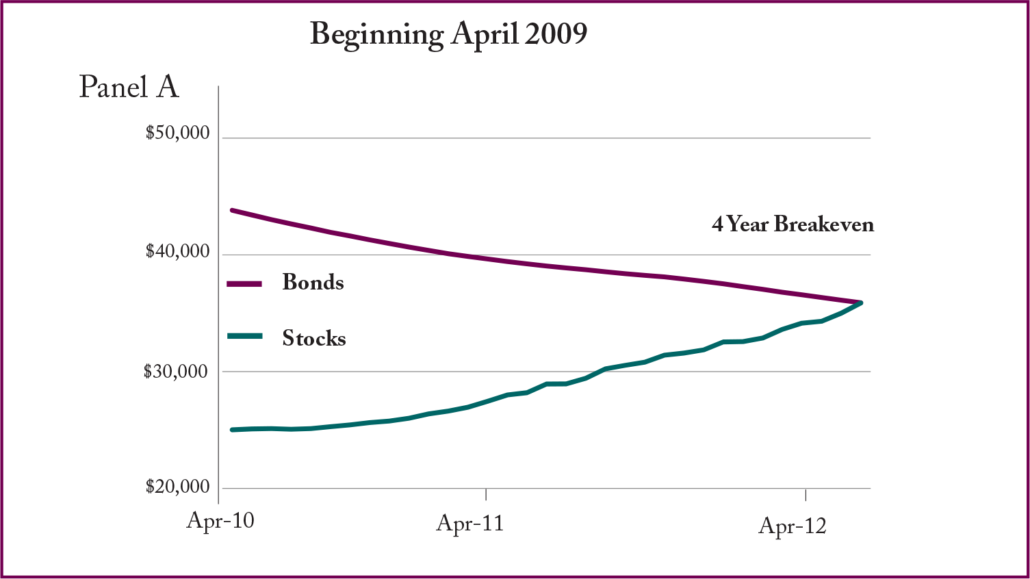

Let’s explore this question starting in April 2009, at the bottom of the financial meltdown. Say you have $1 million with the goal of living off your investment income. You can invest either in a stock fund or a bond fund. The bond fund earned $41,000 in income over the following 12 months, while the stock fund earned $25,000. Selecting the bond fund seems the obvious choice in order to achieve higher, dependable income, especially on the heels of the biggest drop in stock prices and dividends since the Great Depression.

This first-year income is not the full story though. After the initial 12 months following April 2009, interest rates dropped to levels never seen before, and stocks delivered one of the longest and largest bull markets on record. Of course, no one knew it would work out like this. But this is where we are today. We draw lessons from our experiences, especially our most recent ones.

While we don’t know what the future holds, we do know from long-term experience that most companies raise their dividends over time. This means the income from the stock fund increases in most years, eventually overtaking the income from the bond fund. Starting at the market bottom in 2009, the stock fund took only four years to generate as much income as the bond fund (panel A).

So by 2013, the stock fund was sending you a bigger check than the bond fund. Bad news for income-oriented investors who put all of their nest egg in the bond fund. But wait, it gets worse for investors who chose all bonds over stocks. Investing the same $1 million today (December 31, 2016) will generate income of around $23,000 from the bond fund over the next 12 months vs. $22,000 from the stock fund, assuming no change in interest rates or dividends during the second half of 2017. In other words, not only do stocks deliver income growth, they are generating almost as much immediate income as bonds – plus offering appreciation potential.

Little wonder some investors are asking: Why buy bonds?

A Long Time Ago

in an Investment Galaxy Far, Far Away…

Let’s go back in time to 1976 and explore a contrasting “why” question when the investment world was different. Apple Computer launched this year, one year after Microsoft booted up. The very first index fund, Vanguard 500 Index Fund, started trading. At the same time, the stock market was treading water. The Dow crossed 1,000 after initially surpassing this level in 1972 and coming within a few points of 1,000 in 1966. Investors would have to wait until 1982 before the Dow stayed above 1,000 for good. Sixteen years of going nowhere for stocks.

What investors grew to believe back then was vastly different than some of the principles investors live by today. There was not the unshakable faith in equities. High interest rates (soon to be much higher) combined with a directionless stock market meant investors had little incentive to load up on stocks. A 1979 BusinessWeek headline actually proclaimed, “The Death of Equities.”

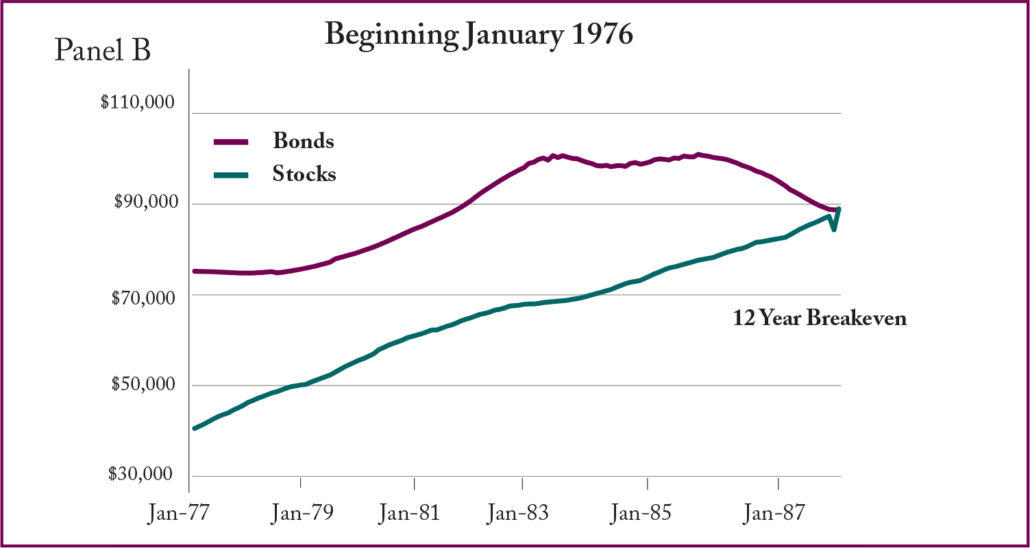

The challenge was particularly true for those living off their income. Beginning in January 1976, our $1 million bond fund would have earned $75,000 for the next 12 months, while the stock fund would have earned only $41,000. Bonds started out with a huge income advantage over stocks, which dissipated very slowly. It took 12 years for the income stream from the stock fund to equal the income stream from the bond fund (panel B, below). Stock dividends were still growing, but 12 years is a long time to wait to catch up.

The question of that era: Why buy stocks?

Different experiences lead to different lessons. Hindsight tells us that the lesson many concluded in the 1970s to buy only bonds was ultimately the wrong lesson. In spite of stocks showing no price gains for 16 years, dividends grew by 5% a year, helping offset cost of living increases. Besides, bonds were only delivering a return of 7%, in line with inflation over 16 years.

Bonds Aren’t Stocks – They’re Not Supposed to Be

Returning to the present day, many take it for granted that stocks will always do better than bonds. Yes, there will be “corrections,” but those are opportunities to buy the dips. Even in the financial meltdown, most buy-and-hold shareholders were rewarded – eventually, of course. The average time to recover from bear markets since 1926 has been three years. Why buy any bonds if you don’t need any of your principal for three years?

Here’s why:

- Hindsight bias: Past drops may seem like no big deal, but it’s different when you are in the midst of a bear market with no crystal ball to be found. Living through it can be painful and cause you to sell at the wrong time – after stocks have taken a big hit.

- Recency bias: Our recent experiences weigh more heavily than lessons from the distant past. Given recent returns, this bias is understandable – but misguided. The stock market’s current valuation is consistent with mid-single digit future returns, not double-digit.

- Volatility’s drag: Bonds, notably short-term bonds, are less volatile than stocks. Take too much money out of your portfolio in really bad markets and your portfolio may not recover as depletion occurs much faster with high volatility.

- Market timing futility: Most stock market gains and losses occur over a very few number of days. The odds of selling out and going to bonds right before a crash (then getting back in right after) are horrible. Trying to time interest rates hasn’t worked well for most investors either.

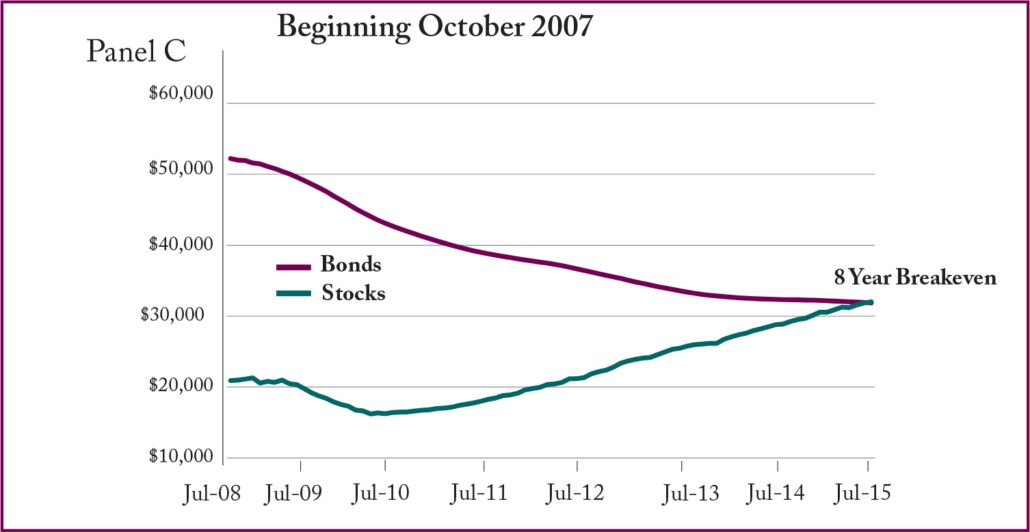

- Dividend risk: In the meltdown, dividend cuts were quite large – totaling approximately -26% from high to low. If you invested $1 million at the top of the market in October 2007, it would have taken eight years for the stock fund’s income to surpass the bond fund’s income (panel C, below).

- Bond-stock connection: If interest rates were to rise sharply, bond prices will drop, but it would likely be negative for stock valuations as well. Changes in interest rates have had and will have a big impact on stock prices.

- Positives of higher rates: For shorter term bonds, an increase in rates places less pressure on prices since maturities are near. Likewise, the benefit of higher income is felt relatively quickly.

With interest rates low and equity valuations high compared to history, both bonds and stocks look to offer positive but below-normal returns over the next five-to-10 years. Nothing to write home about from either one.

History shows the risks of excluding either stocks or bonds from a portfolio.

For most of us, the question we should be asking ourselves is “how much,” not “why”. Given that dividend income is competitive with interest income, the exact answer depends upon how strongly you view the above considerations. Throw in some intestinal fortitude and you have a good recipe for navigating future markets.

Let Trust Company of Oklahoma help you decide what is best for your wealth management goals.

Bob McCormick