COVID 19’s Economic Impact and Investment Insights

By Philip Mock

If there is one adjective which best describes 2020, it is unprecedented. The impact of the pandemic has been without precedent in its devastation to our families and our way of life. For better or worse, in 2020 we all learned how to work from home, how to use Zoom, and what constitutes an essential business. And let us not forget our collective thankfulness for toilet paper.

For investors, 2020 provided its share of thrills. Seemingly, every market phenomenon was packed into the past year. The highs were high, the lows were low, and they alternated at a lightning-fast clip. The speed of those fluctuations left retail investors and professionals alike peering into their computer screens daily, searching for reason. Like most recession years, staying the course appeared to be the best antidote. From the S&P 500 dropping 34% in five weeks (the fastest bear market in history) to rising up over 18% as of this article, the investors who held steady have been rewarded.

There is no doubt that 2020 will be well documented in the history books. From the pandemic, the election, the market volatility, and the recession, writers will have deep wells of storylines and material. When we reflect on the economy in specific, a few themes emerge which are likely to impact investors for years to come.

The Great Rise and Fall of Interest Rates

At the start of the year, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) expected to raise interest rates over the next few years. The Fed was also slowly unwinding its balance sheet by reducing the amount of debt instruments held. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate was at a multi-decade low, inflation was gradually appearing and the overall economy was operating at a gentle trot. Not too fast, not too slow—in another word, precisely where economists like it. Yet, some were concerned.

The economic expansion that had lasted 10 years was growing long in the tooth, and the consensus among economists indicated that a recession was probably 18-24 months away. And then there was COVID-19. In response, the Fed rapidly began dropping rates (specifically, Fed Funds Rate) from 1.5% to zero in the span of only two weeks in March.

Given the likelihood we would end up in recession, the decline in rates was warranted, but still shocking considering the abruptness of the pandemic and the Goldilocks economy at the beginning of the year. The forward implications of the decline in rates is no less notable.

Similar to the decline in short-term (Fed controlled) interest rates, the long-term secular decline in intermediate-term rates reached a record low of 0.5% for the 10-year Treasury bond on August 4. This decline began nearly four decades earlier when the 10-year Treasury reached a high of approximately 15.75% in 1981. Unless U.S. interest rates go negative in the future, it seems likely that the 40-year bull-run in fixed income has come to an end or, at the very least, doesn’t have much farther to fall.

Additionally, since the Fed decided in August to modify its policy objective to aim for average inflation of 2%, as opposed to a hardline 2%, future interest rates and actual inflation will be impacted. Historically, the Fed raised the Fed Funds Rate as a way to combat inflation. But now that the Fed is content to let inflation creep up for a while, it is likely to raise rates more slowly than it has in the past.

In the words of Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, “[F]ollowing periods when inflation has been running below 2%, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2% for some time.”

The Fed is suggesting that interest rates are likely to stay put for at least the next two years. The dot plot, a graph of the FOMC’s voting members’ predictions for future interest rates, doesn’t indicate a meaningful possibility of rates rising until beyond 2023. This represents about a 2.5 percentage point decline from where the Fed originally expected rates to be in 2022/2023, based on how it voted prior to the pandemic. Lower interest rates will be a continuing theme for years to come.

Borrow like it is 2020!

Needless to say, the federal government’s response to the pandemic and recession has been expensive. Various forms of fiscal and monetary stimulus plans have resulted in the U.S. taking on a significant amount of debt.

The federal government added about $3 trillion to its balance sheet — similar to the amount the Fed added to its balance sheet. In addition, Congress recently passed a new $900 billion stimulus package that will further increase U.S. debt. The U.S. is not alone. Virtually every major developed nation borrowed to pump money into their economies to shore up families, companies and municipalities. Furthermore, central banks such as the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England all proportionately increased the size of their balance sheets as well.

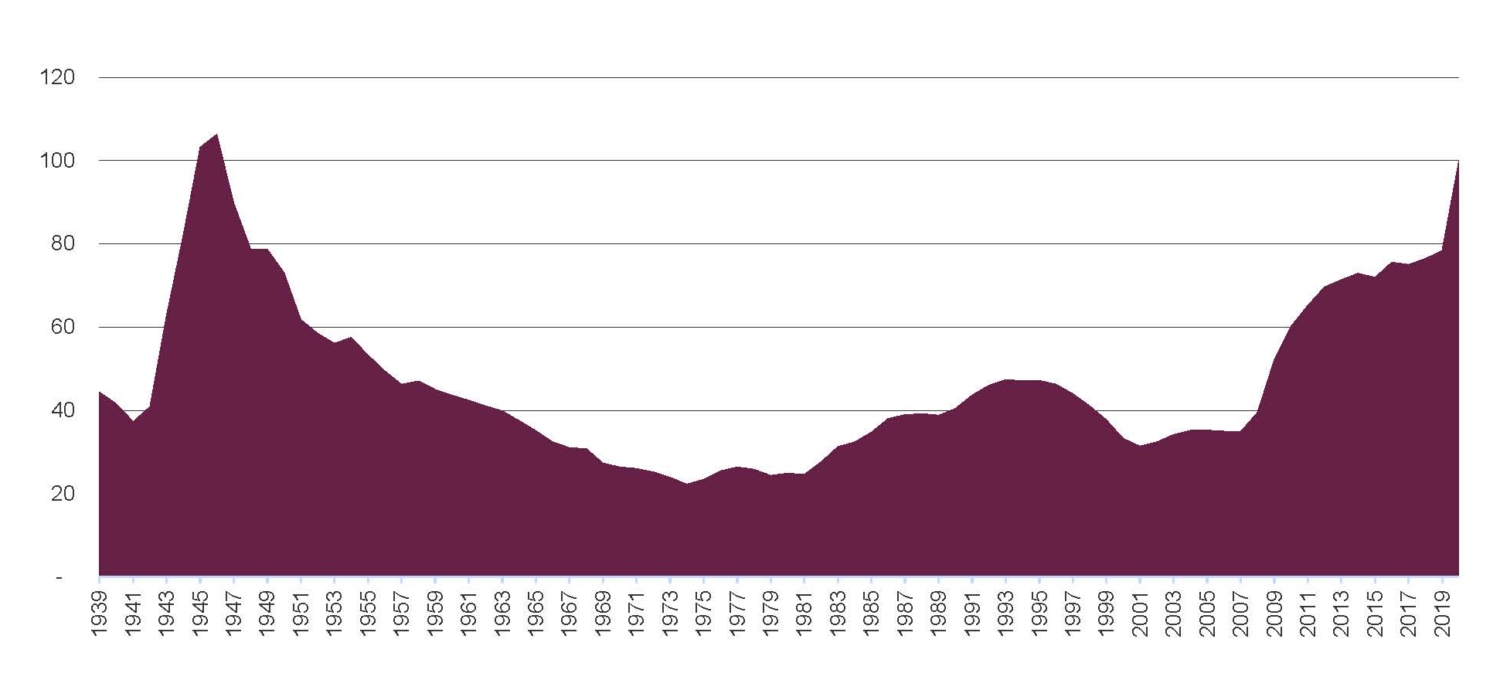

Although such borrowing has occurred in the past, it is rare. Typically, only wars produce the levels of government borrowing we have seen in 2020. Speaking of wars, after World War II, the Federal debt held by the public as a percentage of our GDP (encompassing all of public debt; not just that held by the Fed) eclipsed 106% in 1946 and fell to a low of 22% in 1974. Since then, we have been on a sustained borrowing spree and are set to end 2020 around 100%, up from 78% at the end of 2019 (see graph below).

Debt Held by Public as % of GDP

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

From an academic sense, the downstream implications of such a large debt load could include higher inflation, a lower U.S. credit rating and stunted future economic growth. Time will tell what is in store for the United States. Regardless of what happens, it will take time to unwind the sheer amount of debt the Fed has taken on in 2020. For perspective, once the Fed began unwinding its balance sheet in early 2018, it took about 21 months to unwind $750 billion dollars. At that same rate, it would take the Fed nearly five years to unwind the debt taken on this year alone. The debt incurred in 2020 will not disappear overnight and will be something the Fed will contend with for several years at least.

Weakening of the Dollar and International Stock Trends

From December 2016 to May 2020, the dollar fluctuated, ending down about 2.7% from the December 2016 level. However, since May of this year, the dollar has weakened about 11%, a substantial change for a currency over a relatively short period.

As a result of the weakening dollar, international stocks, especially in emerging markets, are the recipients of a currency-driven boost they haven’t felt for years. In fact, over the last six months, emerging market stocks have outperformed the S&P 500 by almost 8%.

The question is: will this trend continue? We have seen other “head-fakes” over the last 10 years. The value of the dollar is typically dictated by market forces more than economic intervention or activity, which makes it truly a zero-sum game. The future of the dollar is nearly impossible to predict, and betting on it directly has humbled many professional investors over the years. Yet, history does offer some guidance. Additionally, a few developments in 2020 favor the story of a weakening dollar in the months ahead:

- Relative Interest Rates: Over the last several years, interest rates in the U.S. have been superior to those of other developed nations, including Japan, the U.K., Germany, France, Italy and Canada. Although the U.S. still has more attractive interest rates than these countries, the decline in rates over the past year has narrowed the spread considerably. For those looking to invest globally, investing in dollar-based debt is not nearly as attractive as it once was.

- Our Trade Position: As a result of the pandemic, recession and related factors, our trade deficit has substantially worsened this year. The U.S. relies heavily on trading activity, especially from China, Mexico and Canada. Our trade deficit across all trading partners is at the widest level since 2006. The tariffs implemented several years ago have had a mixed effect in managing the deficit and will likely be unwound by President-Elect Biden. Typically, such a trade position points to a weakening dollar as the amount of money leaving the U.S. to buy imports continues to exceed the amount of dollars entering the U.S. as a result of selling exports.

A weakening dollar isn’t necessarily all bad. Manufacturing exporters would benefit from a weaker dollar as it makes their exports more internationally competitive. Companies that have moved operations overseas may consider moving personnel back to the U.S. if it becomes relatively cheaper due to a weakening dollar.

Risk Considerations of Bitcoin Investments

All of the aforementioned economic trends will undoubtedly impact the market. Despite the challenges, it seems reasonable to expect the market to still generate positive returns in the coming year. The actual magnitude of those returns, however, will largely depend on the success of the vaccine rollout and associated return to normalcy. The economy should continue its recovery and will hopefully return to it’s pre-COVID track within the next two years.

Though 2020 presented many challenges, it also reminded us of our many blessings — with family, friends and healthcare professionals at the top of the list. While we have always been grateful for you, our clients, the challenges of 2020 made our appreciation for your trust and relationship that much sweeter. Here’s to much happiness and health for you and yours in 2021.

Philip Mock

Executive Vice President & Chief Investment Officer

(918) 744-0553

pmock@trustok.com